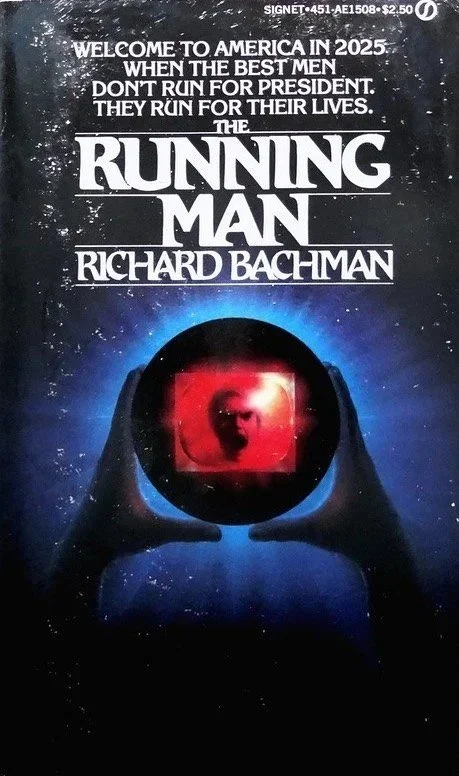

The Running Man

The Running Man

By Richard Bachman

Since a friend and writing colleague of mine told me she wants to go with me to see the new movie remake coming out, I decided to sink my literary teeth into The Running Man by Richard Bachman. And while it’s no secret that there is no Richard Bachman—only a pseudonym made up by Stephen King—I feel like it’s only fair to judge this book as if it were written by someone else.

But, first, why did King need to be Bachman?

Back in the 1970’s and 1980’s, there was a stigma in the literary community if a writer pumped out a lot of books in a short amount of time. King had once stated in an interview that it was considered pushing bad writing/poor product in order to make a quick buck if you were a novelist who published more than one novel in a year. While it’s not as different today (with rumors circulating about big names like Patterson using ghost writers to push product), some agents and publishers used to encourage authors to use pen-names to publish on the side in the event they had multiple manuscripts to sell. That was part of where Bachman came into play.

The much larger part of being Bachman, as described in King’s essay “The Importance of Being Bachman,” came from King’s love of storytelling and almost-insecurity that his darker stories wouldn’t be as well-received given the brand he’d made for himself. Much of the Bachman collection is comprised of earlier works—manuscripts written by a younger writer full of enough anger and passion that they push boundaries. Show us the darker side of humanity. And, sometimes, remind us that good doesn’t always triumph over evil. King reports that—in that manner—Bachman is almost like a different person.

And I happen to agree with that. So for the sake of any analysis on King’s Bachman tales, I feel compelled to treat them as if they were written by another writer altogether. For reasons you’ll soon understand.

The Running Man is the first Richard Bachman novel I’ve ever read. But it won’t be the last, mainly because it’s the kind of book that’s deliciously dark in every essence of the word. Written in a span of only 10 days, Bachman’s novel is like a bullet to the soul. It doesn’t waste large amounts of time with setup or explanation in its exposition, as Bachman opts instead to cut right to the chase—the inciting moment where its protagonist Ben Richards decides to leave his home to begin his death walk to the Games Federation Building, where he hopes to be chosen to appear on one of its many gladiator-esque game shows to win prize money for medical care for his pneumatic infant.

And it continues that way with very little excess to its bare bones, gripping the reader and refusing to let him go until the close of the book. The novel—as scrawny as its protagonist—is barely 300 pages of pure action, following Richards as he moves from one obstacle to the next in his efforts to not only help his family but also stay alive. The result is that, while highly entertaining, Bachman’s story packs an overabundance of energy which is almost overwhelming from a thematic standpoint. At times leaving the reader wondering what they’re supposed to get out of the novel after its conclusion. It was only after careful contemplation (and rereading some passages altogether) that I was able to tap into what grand vision of theme Bachman was trying to achieve.

If Stephen King is the literary horror equivalent of the full-course meal, then Richard Bachman would be the equivalent of a parent allowing you to have ice cream for dinner—filling in the moment and exciting but nothing sustaining long-term. A thrill ride that is a page-turner but doesn’t feel as well deserved. It’s not that Bachman’s themes of inescapable circumstances/control and government/media manipulation aren’t important or can’t carry weight. It’s just that—from a craft point of view—I wanted more engagement with that. I wanted greater layers of depth intermixed that I felt the experience gut me like a dead deer carcass. And sadly, Bachman did not deliver that.

That being said, what Bachman did deliver was passion and anger and energy—enough so that you could feel enough of what the protagonist felt and feel for his circumstances. (Just not enough where it counted—in his engagement with the societal forces against him). Such traits are most notable in young, ambitious writers, and Bachman is no exception in that regard. He comes across multiple times in the text as a passioned man with some powerful messages threatening to burst forth from him if he doesn’t get them out on paper. And, in my mind, that’s the sign of talent (even if some of that thematic energy becomes misplaced in his work).

There were several times I stopped and reread passages of The Running Man simply because I wanted to experience the words again, if only to feel the writer’s heat a second time in his descriptions. The ending is one such place, as in my mind, it tied together the passionate and angry tale quite nicely.

At the same time, such speed and energy also caused the work to skate across the waters of characterization at times rather than dive deep into them. While I felt for Richards, I had trouble sympathizing with his wife Sheila or some of the side characters (Elton, for example) because there was so little glimpse of them throughout the story that they read almost place-holders for the protagonist’s motivation. As if they were starter fluid to get the great novel engine going and were dropped by the wayside until they were needed again. To me, that detracted from the effectiveness of the work. Since everything tends to affect everything else when it comes to fiction writing, if Bachman had taken the time to repeatedly layer more characterization into the novel, there would have been greater space for The Running Man to engage with its thematic message. That would have meant a longer-lasting gut-punch to the reader, obliterating them with such force that the thematic message would resonate long after the novel concluded.

Regardless, with this being my first Bachman read, I’m interested to know how the other novels stack up. I have a feeling that the talent shown in this book is only further-explored in the other earlier works, the base for the later Bachman books written in the 1980’s. When the two talents finally merged to become one, thus blowing King’s cover forever.

I’d like to recommend The Running Man by Richard Bachman to any fresh writer who is interested in writing a novel but has never written one. Especially those who would like to learn what their passion could form on a page and how it could detract from the message of the story if its energy is displaced. This book has forced me to look hard at my own written manuscript several times while reading, showing me my own faults in my efforts to learn the wonderful art of novel writing. For that reason alone, I intend to read it again someday.